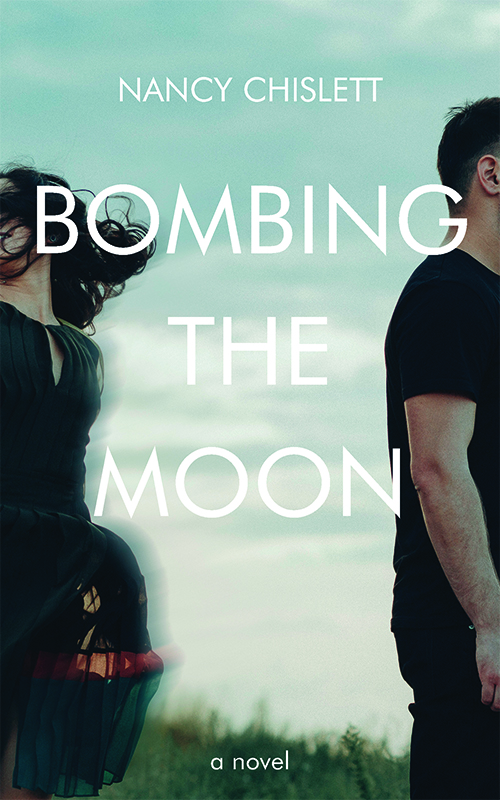

Nancy Chislett

THE OFFICIAL SITE

Release Date – April 15th, 2022

Book launch: April 22nd at McNally Robinson Booksellers,

Grant Avenue, 7 pm

At 24, Devin Rush’s future is unknown and his parents don’t support his dreams of becoming a songwriter. Add to that North Korea’s nuclear threats, a corporate world of greed, and impending automation, Devin feels like the world is rigged against him.

Conflict boils at home. Devin is jobless and antagonistic. His parents, wondering if he’ll never man-up, fear he’ll depend on them for life. But when Devin’s grandfather gives him a one-way ticket to Nairobi, he sees no choice but to leave, and then he’s thrust into a world unlike any he’s ever seen.

Stunned by his sudden departure, Devin’s family is pushed further afield of the control they crave. Resentment and guilt nudge his parent’s marriage closer to collapse, and abandonment triggers his sister’s long-buried shame. When Nairobi’s election approaches and tensions erupt, Devin is faced with choices and consequences that are all too real. Bombing the Moon explores the promises and limitations of tough love.

Testimonials

Over a hundred and thirty years ago a certain (great) writer-to-be walked into his mother’s hotel room in Normandy and said, ‘Maman, I’ve just spent the most delicious hours reading!’ Exactly how I felt when I finished Nancy Chislett’s Bombing the Moon, a book, by a truly gifted writer, as eloquent as it is pertinent: a representation of the meaning and pain behind the contemporary phrase ‘problems of the first world’ and how they are transposed to what, using a less contemporary term, used to be called ‘the third world.’

Getting to read Nancy Chislett’s manuscript of her novel Bombing the moon, is one of the highlights of 2020 for me. The story, set in Nairobi and Winnipeg – two settings Chislett knows and loves – is one that leaves no illusions about the danger an ordinary Canadian family can face when grandfather Bill attempts tough love on their son Devin by sending him to Kenya to “grow up.” It’s not just peril in Nairobi, it is friendship, Bach, love, and joy. But when danger presents itself in Kibera, Nairobi’s slum, the reader will find danger for Devin’s sister and parents living on a swish street in River Heights as well. Chislett knows her terrain and her ability to tell the story of a fractured family in a compassionate yet unsentimental way is the mark of a gifted writer, one who never gets in the way of her characters or their story.

Chislett’s Bombing the moon is subversive and compassionate. Though the author does not moralize, does not instruct, does not come down on one side or the other, the novel gets the reader to weigh the logic of tough love, recognizes the different relationship dynamics where it might be employed, including international politics, and journeys through the affect it has on the thoughts and actions of four distinct members of the Rush family. Bombing the moon contains a high degree of psychological truth that rides on top of a quick pace and finely written action.

Nancy Chislett is an avid traveller, having visited almost 50 countries on six continents. She also plays classical music on piano and composes a little jazz. Career-wise, she has worked as a high school teacher and as a university administrator of an international student program. Bombing the moon is her debut novel, and currently, she is working on her second literary work, entitled, Saving Fictions. She lives in the eclectic city of Winnipeg with her partner, Grant, and dog, Simon.

READ EXCERPT

BOMBING THE MOON

We walk in silence, down what might be Kibera’s main street, and veer down a path that takes us between dwellings. The path is the width of a man, and a shallow sewage gutter carves a vicious backwater reek. “Have to catch my breath.” I say. “Want me to hold your bags?”

I shake my head and lean against a wooden wall.

“It’s not Marrakesh rancid, but that’s not the problem with you, mate. It’s the bag of bricks been dropped on your head called culture shock.” I nod with eyes shut. “When they tire of Spain, the British pay big money for that sensation. You should see the old ladies around Marrakesh’s Djemaa El Fna. They hide in the tea shops and revive with pincushion pastries.”

We troop forward. The path fills with people. Their faces pass and looks are exchanged and some are indifferent and others seem sore. Mostly, I’m keeping my eye on Paul. I don’t know how he knows where to go in this labyrinth. But then, he knows so much. Like how Africa is a continent, not a country. That the population in Nairobi rises by as much as a million per year. That terrorist attacks and terrorist hreats explain the extra security everywhere. That businesses sell goods in single-use plastic and that’s the garbage everywhere. And some people wash away during heavy rains, when the floodwall collapses along the shore of a river.

We come across a door. It’s fabric that reminds me of what Indian women wear. An elderly man parts it and lets me pass before stepping out. For a split second, I glimpse his existence—a mattress stowed in the corner. The fabric door drops. I step past a group of serious young men bent over a chess game. Their eyes lift as Paul approaches, fall on me, and return to the board.

A woman with two small children tucks one under each arm and scurries down the path. When I turn to see where we’ve been, I see I am being watched. A boy, maybe five years old, wears a grey suit stained with mud. Clasped in his hands is a handful of plastic bags. He doesn’t speak. Just holds the bunch out to me. Paul is getting further ahead. I turn away.

Finally, a clearing. Sparks from a fire zip through the air. Paul looks past me and pans right. The alleys are tight again, and I can’t see past him until we are free. Another slope, and soon we’re standing on a mound speckled with grass. Somewhere, a woman screams. Paul moves toward one of the hovels with a pallet-like door. There’s crying coming from inside. Something in his face changes. I glance around. No one is doing anything. The door bursts open. A young black woman flees with something in her arms. The crying inside continues. It’s coming from a young woman lying in the shadows. The taste of iron is in the air. The lower half of her dress is wet with blood. Her eyes find mine. An older woman wipes the woman’s forehead with a dripping cloth. I hear moaning. It’s weak and guttural. I realize it’s me. Mooing like a sick calf.

“Sorry, mate,” Paul says. “There’s a doctor’s strike.”

He takes me by the elbow and leads me out. I totter sideways. Paul takes me to a quiet spot and claps my cheeks. “This is it, isn’t it?” His voice goes high on “it,” as in, “beautiful, isn’t it?” He releases me and shakes his fist at the sky. “This is the real shit. When’s the last time you didn’t worry about a bunch of soul-deadening minutiae? Rent. Bills. Here, all that recedes.”

I drag a sleeve across my eyes. “It’s nuts that people live like this,” I say.

“It’s perfect sanity. When corrupt politicians are done with you, it’s the only sane response.” His finger wags at the bypass. “Out there is nuts. I knew when we met, I said to myself, ‘Now here’s someone who can roll.’ You’re not hung up on the details.” If this is Paul’s idea of a pep talk, I’m not sure it’s really about me. His eyes are two burning suns. “I mean, most well-to-do Kenyans wouldn’t come here. Now look at us. Anyone could kill us. We’re living on 100 percent trust. Have you ever felt so awake?” His enthusiasm is hard to resist. I find myself watching his body, his face. The constant hum of his mind. Can he see me in him?

“Welcome to the watering hole, son.”

Latest Posts & News

CHECK MY BLOG PAGE TO READ RECENT POSTS AND UPDATES ABOUT MY NOVELS

Book Chat with the Manitoba Writers’ Guild

Autumn has begun and that back-to-school spirit is in the air. After a break in July, I'm back in my office writing the second half of a second novel that I haven't settled on a title for yet. It's...

One literary book review in Canada

First, you should know that the experience of being reviewed doesn’t even start with a book review. You can write a novel, have it published with a traditional publisher, have a book launch, hit...

Writing a literary novel told by multiple points of view

It’s the most difficult kind of novel to write. Writing it is awful. Kidding. Somewhat. Writing a novel with multiple points of view comes down to faith; faith that the story will come...